On the first floor of the magnificent Musée D’Orsay you will find an imposing bronze of Count Robert de Montesquiou, once the arbiter of elegance in Paris society. Appropriately it stands in front of a portrait of his contemporary Marcel Proust by Jacques-Emile Blanche. Paul Troubetzkoy’s 1907 cast highlights the subject’s haughty profile, his arched silhouette, his slender fingers and the intricate design of his outfit.

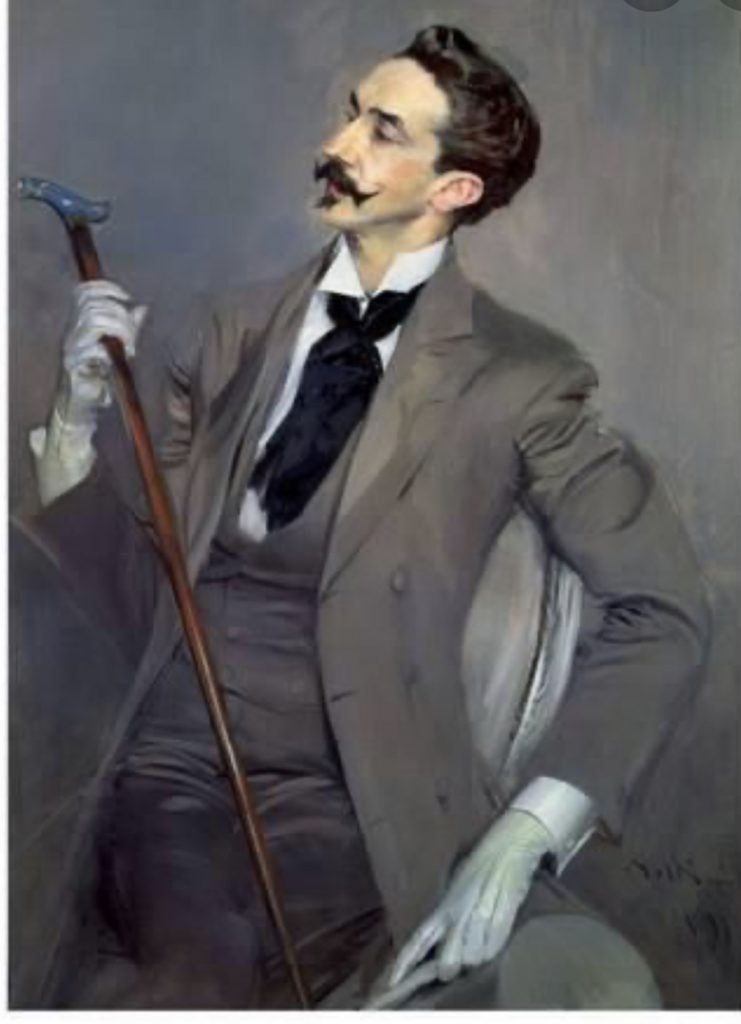

Troubetzkoy was not alone in capturing this extraordinary dandy for posterity. His sculpture of the Count was a three-dimensional equivalent of coveted portraits by the Anglo-Hungarian Laszlo, the French La Gandara, the Americans Whistler and Singer Sergent, the Swiss Louise Breslau and the Italian Giovanni Boldini. The latter’s immortal portrait of the Count has him seated, in profile, the diagonal of his body counterbalancing that of his cane, in shades of gray.

Montesquiou’s idiosyncratic behaviour was the stuff of dreams for a sculptor whose own life was no less quirky. At the beginning of any conversation, the dandy would remove one glove and launch a series of gesticulations, raising his hands towards the sky, lowering them to touch the tip of one perfectly buffed shoe, or waving them as though conducting an orchestra. It is said that Montesquiou would burst into the laughter of an hysterical woman, then clap his hand over his mouth to quieten himself. Most likely the reason for this abrupt gesture was that, despite his handsome physique, his teeth were small and black.

Perhaps the most vivid portrait of the Count appears in a delightful 1925 memoir by Elisabeth de Gramont: “Leaning on the railing of my upper balcony one bright spring morning, gazing down onto the Avenue I was suddenly struck by the appearance of a tall, elegant personage in mouse-gray, waving a well-gloved hand in my direction as he emerged swiftly from the green shadow of the chestnut trees into the yellow sunlight of the sidewalk. He must have been in an unusually conservative frame of mind that day to have appeared in mouse-gray. He might, likely as not, have turned up in sky-blue, or in his famous almond-green outfit with a white velvet waistcoat. He selected his costume to tone with his moods and his moods were as varied as the iridescent silk which lined some of his jackets.”

De Montesquiou’s place in contemporary literature is well-known: his idiosyncrasies have been immortalised in the shape of Joris-Karl Huysmans’s character Des Esseintes (A Rebours, 1884), Jean Lorrain’s Comte de Muzarett (Monsieur de Phocas, 1901), Henri de Régnier’s Vicomte de Serpigny (Le Mariage de Minuit, 1903), Edmond Rostand’s Peacock (Chanteclerc, 1907), and above all Marcel Proust’s Baron de Charlus (Remembrance of Things Past). More recently, in Julian Barnes’ prize-winning novel The Man in the Red Coat, Montesquiou was the ultimate example of the aristocrat-dandy. Even in childhood he was surrounded by exotic imagery: for example his grandfather kept rare white peacocks “roosting in a catalpa tree”. Léon Daudet wrote that the Count was an aesthete, one for whom ‘thought is less value than vision”. Daudet described him as being “ageless, as though varnished for eternity”, a description no less applicable to the magnificent sculpture by Paul Troubetzkoy.